Coffee Watch reveals here, here and here a sample of the hostile lobbying that coffee organized against the EUDR, which contributed to Germany and Austria’s agriculture ministers attacking the EUDR.

This harmful lobbying was carried out by the German Coffee Federation representing 4C, Dallmayr, Fairtrade Deutschland, Melitta, Rainforest Alliance, Segafredo amongst others; and by the European Coffee Federation, which represents 700 companies including titans such as ECOM, Illycaffe, Lavazza, Nestle, Starbucks, Tchibo.

INTRODUCTION

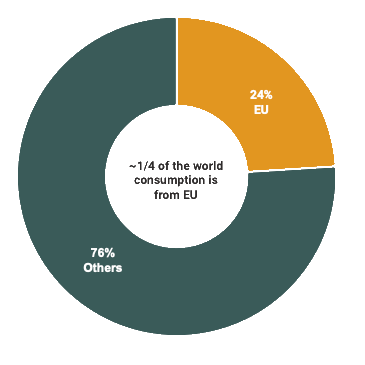

The EU is the largest coffee consumer market globally, accounting for 2.54 million tons of coffee in 2022, which is equivalent to 24% of the total world consumption of coffee.1

Coffee production is associated with significant environmental harms like deforestation and social harms such as slavery, and for that reason is included within the scope of the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR).

The EUDR came under repeated attack from various industry lobby groups in 2024. At the forefront of some of the most bitter and groundless attacks were German and EU coffee industry lobbies. The EUDR has now been seemingly saved by courageous Parliamentarians and others who stood by this vital regulation, protecting it from amendments save for one: a one-year delay that ensures the EUDR will only come into application in January 2026.

In 2025 it will be crucial for the coffee sector to cease its attacks against European regulation and focus on compliance, rather than on thwarting the law.

This briefing provides separate lines of evidence for why it is vital that coffee be regulated by the EUDR, and why coffee companies seeking to undermine the EUDR or find excuses for non-compliance, should not be considered as neutral interlocutors articulating reasonable and data-driven arguments.

Coffee consumer market globally

DEFORESTATION RISK IN THE EU’S COFFEE

In 2018 (the latest year for which data is available), the EU’s coffee imports were responsible for an estimated 14,750 hectares of deforestation, which resulted in 17.2 Mt CO2e emissions from land use change.2

This was the third highest deforestation risk of any of the agricultural commodities imported by the EU, behind soy and beef, and higher than palm oil, cocoa and natural rubber. This is not an accident: coffee spent only one year outside the top five deforestation commodities imported by the EU since 2005.

Arguments that coffee is not an important source of imported deforestation for the EU are unscientific and misguided and should be disregarded by the EU and National Competent Authorities (NCAs).

IS COFFEE LESS TRACEABLE THAN OTHER DEFORESTATION-RISK COMMODITIES?

No special diversity of producer countries

In comparison with other deforestation-risk commodities, the global supply base of coffee is not particularly diverse. The top five producer countries of palm oil and soy produce 92% and 86% of global production respectively, whereas the top five producers of coffee account for 65% of production, and those of leather, beef and wood produce contribute 61%, 53% and 51% respectively.3 This indicates that the supply chain complexity of dealing with numerous producer countries is not exceptional for coffee.

The notion that supply chains’ countries of origin are too diverse to allow for compliance in coffee, specifically, is not grounded in facts.

Top Coffee-Producing Countries by 60-kg Bag Production (Dec 2024/25)

Source: United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

No unique challenges due to dominance of smallholder production

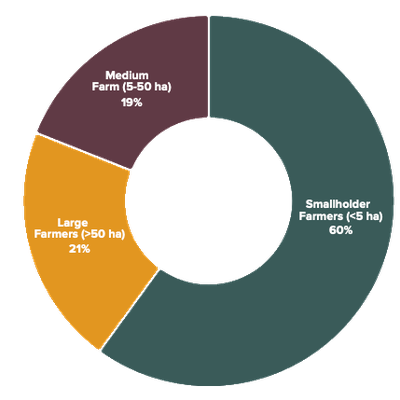

Twenty-one percent of the world’s coffee is produced on estates and large farms over 50 hectares. Nineteen percent comes from estates and farms between 5 and 50 hectares. The remaining 60% comes from 12.5 million smallholder coffee farmers with less than 5 hectares.4

The 12.5 million coffee farmers worldwide represent roughly twice the number of smallholder producers of palm oil, rubber and cocoa5 , indicating an exacerbated challenge for the coffee sector. However, the estimated 60% of coffee produced by smallholders is far less than that in cocoa (95%) or natural rubber (85%), and the overall volume of smallholder-produced coffee is also smaller than that for palm oil and natural rubber, meaning that the challenges of smallholder sustainability apply to a smaller proportion of coffee imports than is the case in some other deforestation-risk commodities.

If the palm oil, cocoa, and rubber industries are able to comply with the EUDR – as they have repeatedly stated they are despite being heavily reliant on smallholders – then coffee should be ready as well.

Global coffee production by farm size

No special supply chain complexity

In terms of supply chain complexity (i.e., the number of steps in supply chains and the diversity of routes to import), whilst every commodity has its own peculiarities, there is no additional structural complexity associated with the EU’s coffee supply chains. If anything, the reverse is true. Unlike many commodities, a large proportion of coffee imports are in a single form and have only undergone primary processing (‘green berries’).

This contrasts with commodities such as palm oil and soy, where primary processing results in a number of separate products; and with leather and natural rubber and a proportion of palm oil and soy imports have undergone several stages processing (and the associated transportation and aggregation) prior to import. In addition, the number of imported products containing coffee is relatively small, compared with soy and palm oil, which are embedded in thousands of products.

Again, on this front as with the aforementioned points, it should be easier – not harder – for coffee to comply with the EUDR.

The importance of provenance helps coffee

Coffee behaves less like a ‘pure commodity’ (i.e., where provenance is irrelevant) than all the other deforestation risk commodities assessed, especially palm oil, soy, beef, leather and rubber. A range of coffees are sold with their countries of origin and sometimes the producers or producer location explicit. This means that there is a significant portion of the market where supply chain traceability is part of the market advantage.

Diversity of distribution to consumers is not a problem

Coffee is both bought for consumption at home and prepared for consumption outside the home. Coffee purchased for home brewing is likely to follow a similar market concentration to the grocery sector in general (i.e., each EU country having a small number of dominant supermarkets). In contrast with many other deforestation risk commodities, there is a huge number of outlets selling the final product - brewed coffee. These include branded and independent cafés, restaurants, bars, institutional cafeterias, cafés in leisure centres, etc.

However, the EUDR places the formal responsibility for compliance on the company that first places a product on the EU market (the ‘operator’), so the diverse routes to coffee consumption do not fundamentally affect how workable the legislation will be for the sector.

Systems already in place to support EUDR compliance

Multiple groups – industry, civil society, certification schemes, and more - have produced extensive guidance for EUDR compliance across most of the regulated commodities. Whilst the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and High Carbon Stock Approach (HCSA)’s EUDR compliance guidance for palm oil stand out, as does the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)’s guidance for the pulp/paper/timber industry, and Global Platform for Sustainable Natural Rubber (GPSNR) members’ guidance for rubber, the cocoa industry and groups in its orbit such as European Forest Institute (EFI) have published the most comprehensive and valuable guidance. Moreover, groups like WWF have produced important cross-commodity guidance on EUDR compliance. Even the Dutch authorities have worked with industry and civil society to generate guidance on subjects like soy compliance.

One industry stands out as being often missing in action, unable or unwilling to publish accepted, high-quality guidance for EUDR compliance: coffee. This must be remedied, perhaps by one of the numerous well-funded platforms that already exist to bring the coffee industry together ostensibly for sustainability, such as the ‘Sustainable Coffee Challenge’ or the ‘Global Coffee Platform’.

The coffee industry can leapfrog off of what other industries have put forth for EUDR compliance guidance, and work quickly to move forward on obeying the law.

Voluntary Sustainability Systems should give coffee an advantage

The coffee industry should be helped in its EUDR compliance journey by the fact that over half of the world’s coffee is covered by a certification scheme. A number of Voluntary Sustainability Systems operate within the coffee sector, including Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance (now fused with UTZ), and organic. In addition to these well-known third-party certification schemes in coffee, some lesser-known schemes like C.A.F.E. Practices and 4C play a major role. An estimated 55% of global coffee supply was certified in 2022. This figure is complex to interpret in that it is a theoretical maximum, as it does not exclude coffee certified by more than one scheme, whilst on the other hand it may be a minimum figure for the EU, which is the largest market for sustainably certified products globally. Either way, it indicates that a high proportion of coffee is already certified.

Most coffee certification schemes have claimed for years that they deliver on traceability, environmental protection, and other sustainability criteria. If what they have said for years is true, then the dominance of certification in coffee should give it a major competitive advantage over other less-certified commodities like rubber (under 1%) or cattle (0%).

Coffee should be more EUDR-ready than other commodities, not less. Even uncertified coffee players should be better able to learn key lessons from certified coffee companies, given the prevalence of certification in the coffee space overall.

More importantly, though, in 2021 just 26% of the certified coffee was purchased as such, with the additional 74% rest marketed as conventional (non-certified) coffee1 , meaning that the sector is not even close to exploiting the advantages of voluntary certification to ensure that production is deforestation free and legal.

Whilst we do not argue that certification guarantees EUDR compliance automatically (due to the varying rules of the systems with regards to deforestation, and the different levels of supply chain traceability that the systems offer, and flaws in their auditing/monitoring practices), the large volume of certified coffee provides some of the key building blocks for EUDR compliance. These include:

- Legal compliance. All of the above certification schemes claim that they insist on and verify compliance with local legislation in the producer countries.

- Deforestation. Most coffee certification schemes claim that they exclude deforestation and verify that the products are not associated with deforestation. Whilst the details vary slightly between schemes (e.g., on what constitutes deforestation for the purposes of the scheme, the cut-off date, etc), and may not be identical to the requirements of EUDR, the verification process of voluntary certification schemes means that certified coffee can be regarded broadly as on track for low deforestation risk compared to non-certified coffee.

- Supply chain traceability. Certification schemes typically operate a number of verified supply chain systems, including identity preserved (where the provenance is known from farm to cup); segregated (where all certified material is kept separate from non-certified material), even if the provenance of farms is lost; and mass balance (where certified and non-certified coffee is mixed, with the proportion that is certified claimed in the mix as such). Identity preserved coffee already has the relevant information required for EUDR due diligence, in effect proving that it is possible to market coffee that is compliant with EUDR traceability and transparency requirements.

- Known producer locations. One of the fundamental building blocks of the EUDR due diligence requirements is having spatially explicit polygons of all producer farms. All voluntary sustainability systems maintain records on their certified producers, increasingly including geospatial polygons. This means that a significant data requirement for EUDR compliance is already at least partially available.

Furthermore, voluntary sustainability systems such as 4C and Fairtrade have developed explicitly EUDR compliant processes for coffee, or are well on the way to doing so.

Coffee companies often handle multiple deforestation risk commodities

There are, of course, many companies that deal only in coffee. However, amongst the main importers (operators) to the EU market there are many companies that import a number of commodities that are within the scope of EUDR. These include the major agri-commodity traders such as Olam, ECOM, Louis Dreyfus, Touton, amongst others. These companies are already preparing for EUDR compliance across their businesses, including in commodities that are at least as challenging to achieve compliance in as coffee. The same can be said of major manufacturing companies (e.g., Nestlé) and supermarkets.

Coffee companies have progressed towards EUDR compliance

Many of the major coffee companies in the EU have existing – and often long-established – commit- ments to exclude deforestation from their coffee supply chains and/or are explicitly working towards EUDR compliance. This includes Nestlé, JDE Peet’s, Starbucks, as well as the companies mentioned in the preceding paragraph. Whilst the specific formulation of EUDR will undoubtedly create administrative and process changes to the implementation of these policies, the sector has in effect had years to exclude deforestation from their supply chains. Furthermore, a number of coffee com- panies have explicitly implemented processes to meet EUDR requirements. These include Neumann Kaffee Gruppe and DR Wakefield, and EUDR compliant coffee is already entering the EU market.

Companies cannot ‘have their coffee and drink it too’: they cannot commit to being deforestation-free, but then argue that they are unable to comply with the EUDR. If they committed to being deforestation-free coffee companies or to being certified as such, then they ought to be in an excellent position to comply with the EUDR.

On EUDR compliance, coffee companies must protect and uplift smallholders

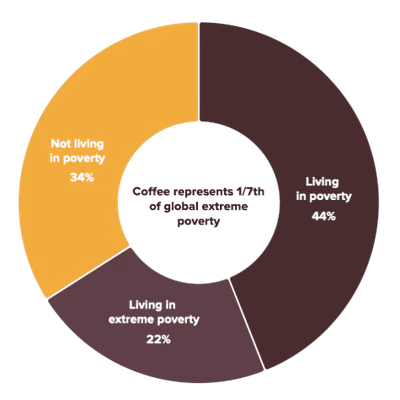

The delay to the implementation of EUDR has given all sectors, including the coffee sector, more time to prepare for compliance. It is also an opportunity to put in place the investments necessary to lift coffee producers out of poverty. Currently, 44% of the world’s coffee smallholders are estimated to live in poverty, and 22% in extreme

poverty.6

Level of poverty among farmers

The coffee industry has an opportunity to “ensure a just transition for smallholders towards sustainable, rights based and deforestation-free practices – without lower- ing the bar of the proposed requirements. This means that smallholders should not bear a disproportionate burden for compliance and/or be pushed out of the market. They should also be paid adequately for their products and supported to meet the EU requirements.”7 Coffee companies must support their smallholders’ compliance with a living income, long-term contracts, targeted investments, technical and financial support to build capacity of smallholder organisations to manage required data. Companies should not choose abusive disengagement with smallholders as an “easy” risk-mitigation measure.

CONCLUSION

The bottom line is: coffee consumption in the EU has long carried within it a dark secret of embedded deforestation. Many coffee companies have been complicit in vast quantities of forest destruction, for decades. A number of coffee industry voices were particularly bitter about EU regulation to curb the problem. They led the charge to try and destroy the EUDR – a vital law designed to save global forests before it is too late. Now that efforts to water down or combat regulation have come to naught, the coffee industry must cease attacks, excuses, and delays.

It is time to wake up, smell the regulation, and comply with the law. The industry is well-positioned to do so, and as this paper shows, is at no disadvantage relative to other regulated sectors. Let’s end deforestation in coffee.

Footnotes

-

Sjoerd Panhuysen & Frederik de Vries (2023). Coffee Barometer 2023.

↩ -

Florence Pendrill, U. Martin Persson, Thomas Kastner & Richard Wood (2022). Deforestation risk embodied in production and consumption of agricultural and forestry commodities 2005-2018. Chalmers University of Technology, Senckenberg Society for Nature Research & Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5886600

↩ - ↩

-

Enveritas (2018). How many coffee farmers are there in the world?

↩ -

Palm oil; soy: Vivek Voora, Cristina Larrea, and Steffany Bermudez (2020). Global Market Report: Soybeans. IDS.; cocoa and Neville N. Suh, Ernest L. Molua (2022). Cocoa production under climate variability and farm management challenges: Some farmers’ perspective, Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 8, 100282, ISSN 2666-1543; rubber: Inkonkoy, F., (2021). Sustainability in the natural rubber supply chain: Getting the basics right. SPOTT. London: Zoological Society of London.

↩ -

Rushton, D. (2019). Bringing Smallholder Coffee Farmers out of Poverty. Carto.

↩ -

FERN (2022). Recommendations for a smallholder-inclusive EU Regulation on deforestation-free products.

↩